My students and I built a fiery oven at our school in Athiru Gaiti, Kenya. It has brought us together and satiated our pallets with delicious foods from foreign lands. Welcome to my telling of some happenings and occurrences.

02 April 2010

How to Be Idle

The other day I was supposed to show up for an end of term staff party at noon. I showed up at 1pm. The reason: As I was leaving my house someone invited me for tea and I took tea for an hour.

How should I interpret this? The thing is, I showed up to the staff party an hour late and I was the fourth person (out of ten) to arrive. If taking tea for an hour is a way to be idle, what about taking tea for two hours?

As I was walking to the party I kept laughing at myself. These days I have all but given up trying to adopt Kenyan culture, but it looks like I have been here long enough that I am unconsciously doing it.

24 March 2010

Weekend in Chuka

I have come to realize that left to myself, reading tends to be more enjoyable than cooking or cleaning. I still love cooking, and I can actually enjoy cleaning, but it turns out that what I love most about these two things is doing them for other people. It turns out that I am more likely to visit a friend and cheerfully clean their stove than to clean my own, and I am certainly more likely to appreciate cooking a complex meal when I am sharing it with another person.

Being busy during the school term, I have only really visited Matt, and usually have only gone away from my site for one night at a time. During the same time period, I have found my house getting dirtier and my meals getting simpler. This has been common for me towards the end of the school term. Teaching has now finished though, and I hopped on the bus with Matt to visit a Peace Corps volunteer in Chuka.

Chuka is a beautiful 3 hour bus ride from Maua. It is literally on Mt. Kenya, although much below tree line. The area where she lives is as pleasant as she is and features cool rivers twisting and turning through deep canyons that are leading them off of the mountain. Although the rivers are big by Kenyan standards they are mere streams by American standards.

While we were there we ventured downhill to the river, which included a 100m+ elevation change. I felt so energetic, that I jumped and ran down the steep grade. The weather was so beautiful, the place peaceful, and the company warm. Maybe I should mention that I just reread Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac, which has kindled a little of the zen lunatics playful outlook inside of me. It felt great getting out to a place where no one was watching me so that I could shed my fear of conforming to Kenyan norms and let these feelings flow from me without inhibition.

When we got to the bottom we found a beautiful, clean, and quiet river. AND, there were not any other people there! which is amazing, considering that at every other river I have been to in Kenya I have had the company mothers washing clothes. This river, as you can see in the picture, is far below the rim of the valley, which is where the road and houses are. Inside of the valley there were only crops, and being on a Sunday all of the farmers were in church.

Matt and I waded through the river and hiked cross country to a waterfall that I had seen as we were descending. Then we came back to the river, and finding that there was still no one around we decided to swim! It was more like wading, as the river was only a few feet deep, but we took off our shirts, and were free!

I meditated on a rock, letting the sun dry my back, and I remembered how it feels to have absolutely no worry in the world – it felt GREAT!

I need to remember that there are appropriate ways to be free even when I am around acquaintances or people that I do not know. Heck, I already stand out quite a bit, a little laughter and jumping around cannot make the one mzungu stand out too much more.

I returned to school on that high note, tired, sun burnt, and ready to be with my students; but also ready for the term to end so that I can meditate more and figure out how to keep the energy and the zest with me.

15 March 2010

Science Congress

For all of this term I have been working with a few groups of students on science congress projects. Science congress is the Kenyan version of the science fair. There are several categories that students can register projects in, including physics, chemistry, agriculture, and home science. Within each of these categories they can prepare an exhibit or a talk.

Originally I was supervising exhibits for biogas production, solar water heating, solar water distillation, refrigeration using clay pots, and energy saving jikos (making wood fires that burn less wood). All of these projects were progressing, but in the final days three of the projects dropped and we went to the science congress with the solar water heater and the solar water distiller. Additionally, another teacher advised a mathematical exhibit on construction of a mathematical tool – something like a protractor, ruler, and compass all rolled into one.

At the science congress they asked me to be one of the judges for the physics exhibits. It was great getting a front row seat to all of the presentations in this category. Among the 17 projects in this category was an automatic urinal flusher, a wheel with a light for measuring distance, FOUR different solar water heaters, a homemade bicycle pump, and a homemade record player. The record player was the most exciting until the students revealed that the motor they used did not turn at the correct speed to produce music.

From our three projects, the mathematical tool placed third (one spot away from advancing to provincials), the solar water distiller placed fourth, and the solar water heater tied for ninth. I am immensely proud of the students. They all learned a lot and having our last project rank ninth out of 17 in its category was very respectable. Last year the school did not even go to the science congress but after their experience this year all of the students said that they were going to work even harder on their projects and go back next year.

It is difficult to hold a competition and have every party walk away happy. This year was no different, with claims from my students that they should have placed second and advanced to provincials, or that the judges were generally not fair – luckily they were not talking about me because I did not judge any of their projects.

As a judge and a teacher I believe that the two physics exhibits that are advancing to provincials deserve to go. Unfortunately though, I also saw first hand how carelessly the judges assigned points to our solar water heater. Basically, on the score sheets the other judges did not fill in marks for seven or eight of the points out of the total 50 points. It is not that they marked a zero, they just did not mark anything. Upon reviewing the sheet, the points that they did not assign were for simple aspects of the project such as having a visual aid and stating the mode of presentation, both of which my students did. If these marks were included in the total, our solar water heater would have placed fourth or fifth.

I do not know what the judges motivation was. It was odd that the other score sheets produced by the same judges had the majority of the marks filled.

Regardless of whether the group should have received fifth or if they deserved the ninth place position that they got, everyone from our school is very proud of them.

Below is a picture of Joshua and James waiting to give their presentation on their solar water heater.

02 March 2010

Tea Zone

This Sunday I went up to visit the home of Mr. Gitonga, the mathematics teacher at school. It is located in the tea growing zone, which is separated from the miraa growing zone – where Athiru is located. The separation is mostly along contour lines as the tea requires a cooler climate.

As we climbed up the hill behind his house on foot, I noticed how quiet and peaceful the area is. There was still an occasional drunk, but even in the market place there were fewer young men loitering around than in the Athiru market. As we climbed and began to see the patchwork of tea farms I started to realize that one difference is the population density. The tea farms tend to be 1 to 3 acres, compared to the miraa farms, which tend to be 0.2 to 0.4 acres.

With miraa, someone can survive on 0.4 acres, not well, but they can be able to afford simple food and illicit home-brewed alcohol.

Aside from the population though, the general behavior is different. Later I was talking to another teacher who told me that around Athiru the primary school children work from 4-6am every day before school on miraa farms. In that two hours they are able to earn around 100 Kenya shillings, which is the same amount that someone earns picking tea for an entire day. This relative easy access to money in the miraa zones leads to a significantly higher dropout rate. In fact, out of 200 students that start class 1, it is common for only 10 to finish class 8.

As we climbed higher, Mr. Gitonga told me about how the British had taken the land by force during colonization, but had required that Kenyans buy it back from them upon independence. The Kenyans that purchased the land were the ones who had a little money, were business oriented, and had shares in the factories that processed the tea from white settlers’ farms. The Kenyans that did not have the money to buy land or to pay the taxes that went along with selling tea settled in the lower areas such as Athiru.

As we reached the top of the hill, Mr. Gitonga pointed out the experimental fish ponds dotted into the corners of the tea farms. Apparently a foreign government is giving Kenyans money to build fish ponds. They have a sum of money allocated to each farmer, with included instructions and and materials list. The farmers receive money to pay laborers, buy cement, and then get little fish to start the venture. From the top of the hill, it is apparent that none of the ponds are lined with cement. The imagination is the limit on where this money has gone. From past experiences and from talking to more informed people the situation probably looks like this: the foreign body gives 100 thousand Kenyan shillings for the project. This is a lot of money if you usually make 2 thousand KSh per month from tea. An arrangement is worked out with the Kenyan authority on the ground. 20 000 is spent on labor to dig the hole and lay piping for water. The rest of the money vanishes.

This is not particular to any particular region. These stories are prolific. My favorite is called the “Goldenberg Scandal.” During Moi’s regime, they wanted to provide an incentive for individuals to export goods. There was a man who allegedly imported gold from another country, and then exported it from Kenya, claiming the right to receive the government subsidy. Eventually someone talked, and it came out that the gold never existed in the first place. This man simply paid off the customs authorities to fill out claim form after claim form. In total, he is estimated to have made billions of shillings off of the Kenyan government in this way. No one ever kept track of the documents, and it is unknown exactly how much he made. At the very least, he made enough to build the Grand-Regis hotel, which was estimated to be worth 7 billion shillings.

The real punch-line of the story is that the man responsible suddenly became a born-again Christian and is now a nationally renowned preacher with his own spot on national TV.

These thoughts accompanied me throughout the day, but regardless of the pessimism they created I was very joyous to be in the company of such a good teacher and good friend.

23 February 2010

Founder’s Day

Scouting Trivia: Baden Powell is buried in Kenya.

This past weekend there was a camp out a few kilometers from his grave. I went with 12 of the scouts from my school. We camped together, cooked together, hiked, and did community service together. It was the first time that they had ever been on a scout camp out – and probably the furthest that most of them have ever been from their homes. It rained and they got wet and cold, but they survived and they did not even complain once!

In Kenya, the principal activity of scouts is marching and raising the flag at school assemblies. Most scouts and scout leaders do not know about all of the other components of scouting. While at the camp out I met a few Kenyan scout leaders that are trying to teach them. They are sponsored by an NGO from Denmark to train scout troops. They told me how to get a Kenyan Scouting Association handbook for the scouts, where to buy merit badges, and how to encourage the scouts to continue on their own.

I met a lot of inspired Kenyans on the trip, to which I am grateful. For instance, on Sunday we were planning on remaining at our camp site and then going the next morning. At noon I was informed that we had to leave that day. My scouts mobilized quickly and were able to take down our camp, making it cleaner than the surrounding camp sites, in about half of an hour. Then, as they were finishing, I went to figure out how to get back to school. The public bus that we took to the camp left town at around 12:30, and it was the only direct bus from Maua to the camp, a journey which took us around 6 hours. As I was trying to find a private school bus that could squeeze us and take us I came across a scout by the name of Jean (the first French name that I have seen in Kenya). He spent over half of an hour with me helping me to track down a bus. After all that help I offered him a soda and he told me to buy my own scouts a soda before I considered buying him one. This might well have been the first time in Kenya when someone helped me so much and refused compensation.

Jean’s actions radiated the image of Baden Powell that is ingrained into scouts. My own scouts had never heard the story of the young scout that inspired Baden Powell to spread the scouting movement. I wonder if Jean had, or if even without hearing it, his involvement in scouts helped to shape the same ideology. Either way, I hope that through scouting, and outside of scouting, Jean, myself, and every other citizen can help to mold the younger generation into such enlightened beings.

The bus that we found was for a private boarding primary school. The primary students were trained in all sorts of scouting cheers and songs, and my students loved it. Once we finally arrived back at our school I was exhausted, but the scouts continued to sing the new songs that they had learned.

And some pictures:

The first one shows the scouts’ tent. It is made out of maize bags that have been cut and sewn together into a plastic sheet. There was a lot of rain, and they were soaked. This is scouting in Kenya though. You also notice that they do not have uniforms, which is because a uniform costs almost as much as school fees for a term.

As you can tell, they were super excited about all my nifty American camping gear. Here they are showing us how to use my water filter and MSR dromedary.

On the last day of the camp out all of the scouts go to Baden Powell’s grave, which is located at he outskirts of Nyeri.

06 February 2010

Pizza Party

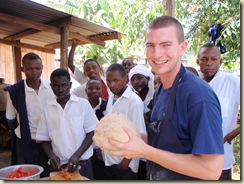

I held a pizza party for the students that scored above a 50% on the end of term exam for any of my classes.

I will give an overview of the process for those of you that have not cooked in a wood-fired pizza oven before.

First, you make the dough, sauce, and toppings. I use normal bread dough for my pizza, although I do not use a recipe, so it may not actually be so normal given the number of iterations that I have gone through.

While one person is making the dough, another person can light the fire in the oven. The fire stays for about an hour and a half. Then, you have to remove the coals. I have had all sorts of accessories made for the oven, including my most recent addition, which is a metal pizza paddle. The pizza paddle was well worth the $4 I paid for it, because it keeps me from burning all of the hair off of my arms each time I reach into the 600 degree Farenheit oven to add or remove a pizza. The way that I used to do it was not good at all.

Then the coals are removed using another locally made tool. I put the coals in a box in order to save them for later use and keep them from smoking all over the place.

Then the pizza is put into the oven. Most people do not use pizza pans, and I may try this one day, but so far I have used aluminum pans that I bought at the local super-store.

The pizza is put into the oven and the first batch only takes about 5 minutes to cook due to the extreme heat. My oven uses locally available materials and does not retain heat very well, but if I wanted to I could cook 3 or 4 rounds of pizza and bread. Although so far I have only made enough dough for 2 rounds.

Then you cut the pizza, let it cool, and enjoy. This pizza is topped with homemade sauce (fresh tomatoes, rosemary, oregano, basil, garlic, ground pepper, hot peppers, salt, a little sugar, etc), onions, squash, potatoes, carrots, and cheese.

Book Report

In part due to having stayed here for over a year life feels normal and it requires more focus to find the aspects that might be interesting to share with people in America.

Classes have started, and apart from getting malaria, I have been doing well.

--------

I have also been continuing to read, and the latest two books, The Invisible Cure and Imperial Reckoning, have been particularly good. The Invisible Cure is about HIV/AIDS in Africa.

In the book the author gives her perspective on the progression of international aid given to Africa to combat HIV/AIDS. What is dis-heartening about the system she portrays is that there seems to be a very low correlation between amount of money given and successful programs. Yet, western countries continue to give billions of dollars a year. PEPFAR, for instance, gives around $500 million per year to Kenya alone and is widely praised at home in America.

The “Invisible Cure” that the author alludes to is, collectively, the mass of locally born programs, which often times do not receive western aid. The directors of these programs usually volunteer and struggle financially to serve their communities, yet they continue to serve despite the challenges. This is in contrast to aid funded programs which have larger budgets, but also have goals designed with as much interest for receiving funding as for serving communities.

Certainly, international aid has improved many peoples lives. For instance, aid, to my knowledge, has been effective at distributing ARVs and, in Kenya, setting up counseling and testing centers. The short-coming of these programs is that they do not feed the many hungry Africans that are receiving the ARVS, nor do they address, in terms that the local population internalizes, the root causes behind the wide spread of HIV in Africa compared to other regions of the world.

--------

The other book, which I am currently reading, is Imperial Reckoning. This book makes me seriously wonder why Kenyans trust any programs that come from the west. The author of the book began investigating the final days of the British occupation of Kenya for a PhD history thesis at Harvard. Through her research she uncovered the story of hundreds of thousands of Kenyans that were tortured – some being castrated or excruciatingly electrocuted. Almost the entire Kikuyu population was put into detention camps or barbed wire villages, where they had no food and no land to farm. Even those that were not in the camps were put onto overcrowded reserves and not allowed to sell produce or cereals in the open market.

This happened here. It happened in the 1950’s. Many of the stories in the book come from interviews with the author. Many Kenyans lives are clearly worse due to the past occupation by the British and yet the many white people here today are not kicked out. This seems fairly phenomenal to me.

An interesting factoid that I learned from the book is that chiefs did not exist, at least in Kenya, before the British. This shocked me because all of my life I have imagined chiefs as being an integral component of tribal society. In reality, chiefs were Kenyans loyal to the British, who were willing to abuse their own people for a share of the profit.

There is so much talk about corruption in Kenya today, but people usually forget the circumstances that led the country to where it is today. For instance, people complain that the courts are not good and that if you want to get your case heard it is likely that you will have to pay a bribe, but most people in my circles do not mention the case of Jomo Kenyatta. The governor of Kenya came up with the idea that incarcerating Kenyatta would stop the spread of the Mau Mau movement. Unfortunately, he did not have enough evidence to convict Kenyatta, so he charged Kenyatta with the ambiguous crime of “managing an unlawful society” and paid a British judge to convict him.

Although most of these atrocities were committed against the Kikuyu, Meru are quick to add that they are closely related to the kikuyu and that generally the bantus were lumped together. Regardless of who was most attacked, the racial fight was ultimately between the white settlers and the legitimate Kenyans.

Knowing the history helps to put this society into context. It also helps to put into context the people who are now purporting to help Africans. With this context it is not surprising that some Africans believe AIDS is a weapon created by white people to destroy Africans.